7a would be for a tetrapod respectively.įollowing the simulations, a rule of thumb for the vanes would be: a Secondary optical component) is supported by a tripod that reachesĭirectly from the cell of the main mirror to the first focus.

The geometry of FigureĦa is often found in lightweight (robotic) telescopes, that carry anĮlectronic camera instead of a secondary mirror. Have very little influence on planetary conrast. Really massive supporting "vanes", that reach into the optical path, Has a three-vane spider of 1.5% mirror diameter. Instrument with 20% central obstruction (left) compared with an Thick, combined with a central obstruction of 20%. Three vane spider that is 1.5% of the diameter of the main mirror Thickness on a 400mm instrument (that is 1.5%) is simulated. In the Figures 5a and 5b the influence of vanes of 6mm Rather often, is the influence of the vanes that carry the secondary Interesting than the central obstruction, that has been discussed (right) again compared to the image with an unobstructed instrument Temperature aclimatisation) are not identical.ĥ0% central obstruction and the resulting diffraction patternĤb: An instrument with 50% central obstruction Should be difficult to figure out at a side by side test, if theĬonditions of the instruments under test (state of collimation, On the other hand, one can imagine that even this difference The apparent diameter of Mars was assumed to be 20" (arcseconds).ĥ0% central obstruction (Fig 4a and Fig. Simulated view of Mars with the unobstructed optical system from Fig.1aĪt a diameter of the entrance pupil (=objective diameter) ofĤ00mm. Test-object, since its surface with the many low contrast features ofĭifferent size is very sensible to a decrease in image contrast of the I used Mars (an image from the Hubble Space telescope) as Obstructions on the image quality bare from different opticalĬonditions of the instruments used normally for such side by side This gives us the opportunity to compare the influence of With exactly this entrance pupil but an otherwise perfect optical The image that would result from imaging an object with an instrument TheĮnergy distribution in the diffraction pattern, we are able to simulate If I were to proceed, I would take $T$ and somehow use it to find the diffraction pattern (i.e., the intensity), though I'm also unclear of the details of that.Diffraction Pattern (Airy disk, right) of an unobstructed circularĮntrance pupil (left), like from a Refractor or a Schiefspiegler. The issue here, is that I'm certain there should be some radial dependence (given that a circular aperture's diffraction pattern has a radial dependence. Then, we'll want to take the Fourier transform of this, which should yield: T = $\delta + \frac)$ (where I've converted the x in the rect function to polar coordinates).

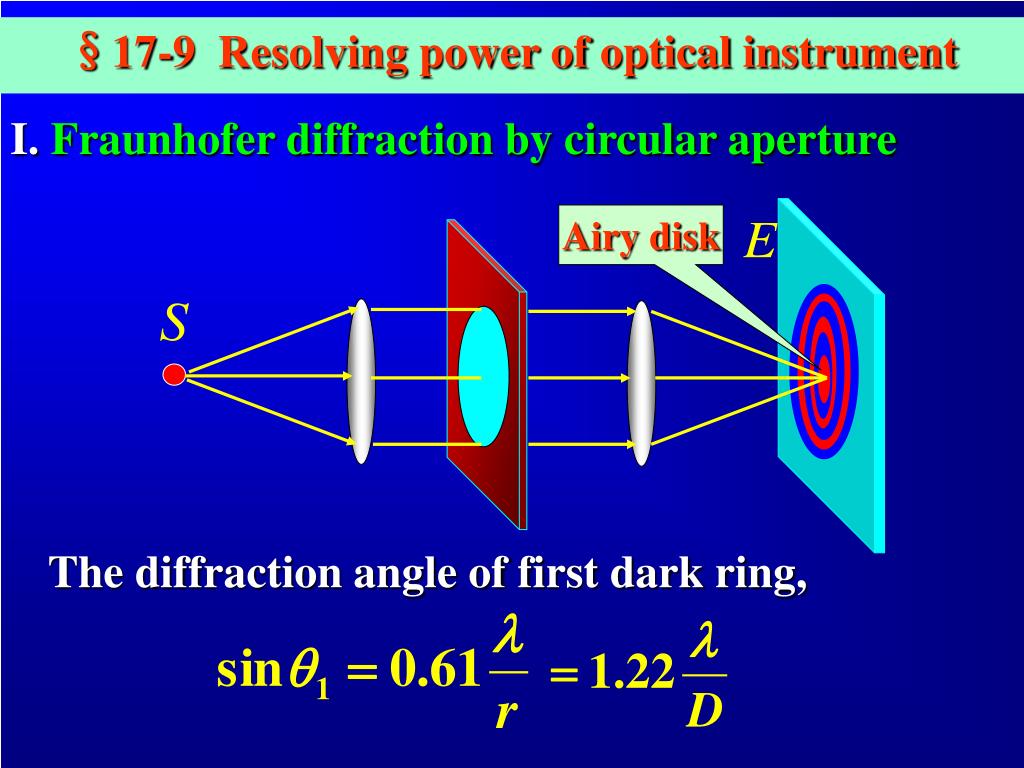

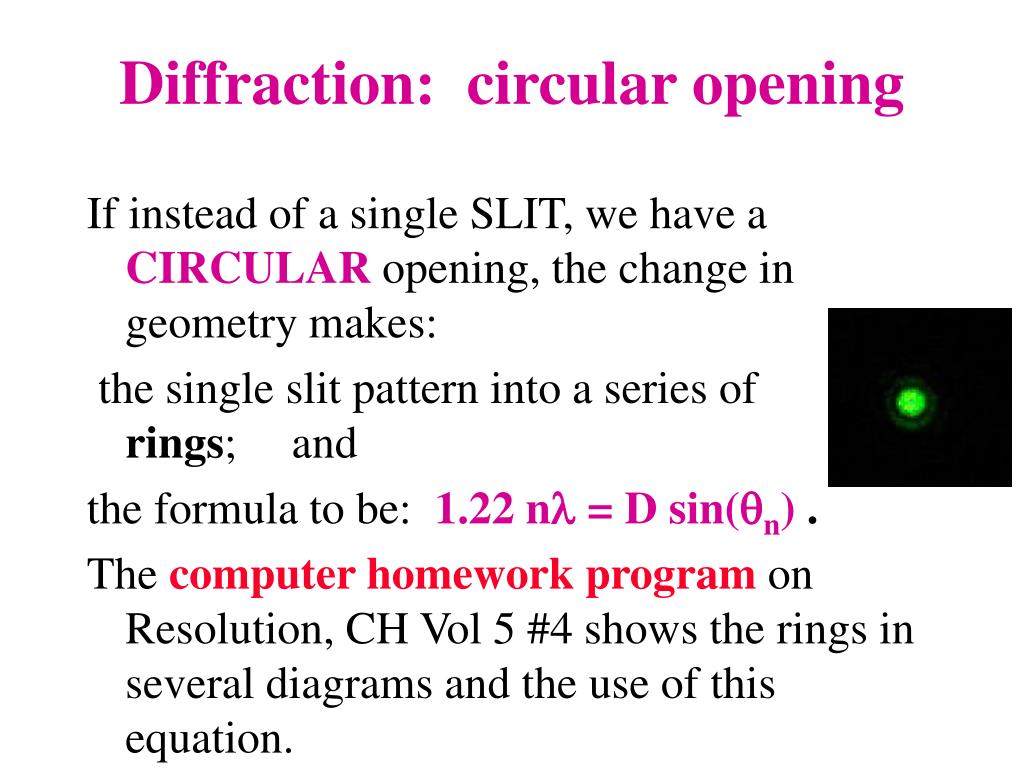

So, the total transmission function should be: $\tau = 1+\Pi(3 \lambda_0)-rect(x/(2*3 \lambda_0))$. The transmission function for a circular aperture is the step function and the for a slit, it is the rectangular function. I understand that to solve this problem, one will have to take the convolution of a circular aperture's diffraction with the inverse of a single slit's diffraction, but I'm having some difficulty getting through the calculation as I'm not entirely confident. What will the Fraunhofer diffraction pattern be in this case?

Suppose we have a circular aperture of radius 3 $\lambda_0$ and we place a vertical rectangle of width $\lambda$ over the center of the aperture (as shown in the picture).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)